I’ve written before about the act of listening, while playing music and as an audience member. My blog post from 2021, The Importance of Awareness, focused mostly on paying greater attention to the musical world around you as a participant, from the physicality of your technique, to the creative use of expression in your playing and awareness of those with whom you are playing in an ensemble.

Today we’re going to widen our listening to the work of other composers and performers.

For most people listening is an activity we do for pleasure - perhaps we allow the music to wash over us as a way of relaxing, or maybe we’re inspired by the virtuosity of professional performers. As a performer and teacher, I’m very accustomed to listening to music in a critical way. That might be in a pupil’s lesson, picking up on both the positive and negative elements of their playing and musicianship. Or it could be while I’m listening to a recording or live performance, noting the way the musicians interpret the music, or how the composer has chosen to structure it. During my student years we spent a lot of time listening in an intentional and active way, because this is a great way to learn how music is composed.

Passive listening can be a wonderful thing, but opening your ears in a more active way can teach you a huge amount - it’s this we’ll be looking at today.

“Music is organised sound”. Edgar Varèse, composer

All the music we play and listen to has a high level of organisation - it’s this that helps us understand it as a listener, whether we do so instinctively or through an understanding of the composer’s methods. But have you given much thought to exactly how a composer organises the notes to create a coherent structure, ensuring the music is satisfying and logical? Perhaps not, especially if you’ve never had a formal musical training. Let’s break these building blocks down into what are often known as the seven ‘elements of music’ - timbre, rhythm, tempo, dynamics, melody, harmony, and texture.

Timbre

This word describes the tone colour or quality of sound in music. Sometimes a composer will choose a particular instrument to play a melody, or perhaps combine several different instruments to create a specific type of tone colour. Each instrument produces its own individual tone colour - the clarity of a recorder, the warmth of the low notes on a violin, the power of a trumpet or perhaps the focused tone of an oboe. Some instruments can also create changes of sound via specific techniques - for instance, a violinist can pluck the strings as well as bowing them, and brass players can insert different types of mute into the bell of their instrument to modify the tone.

Rhythm

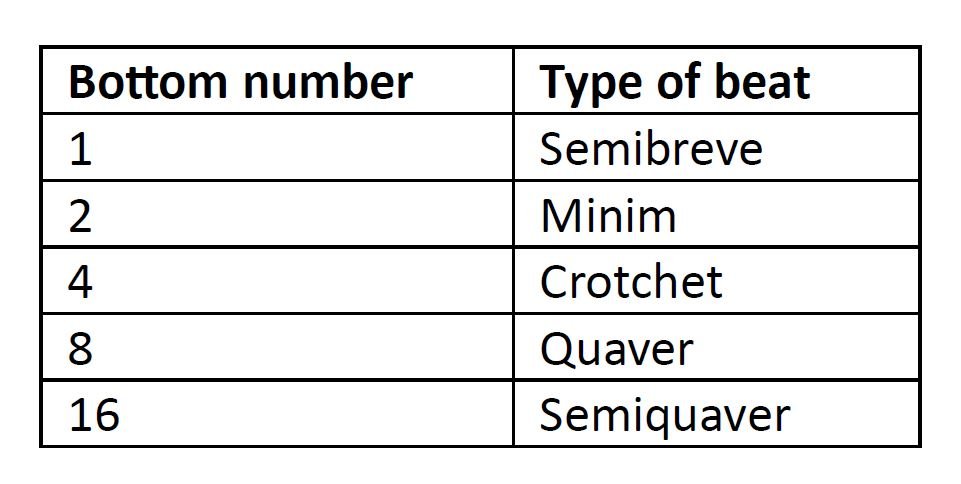

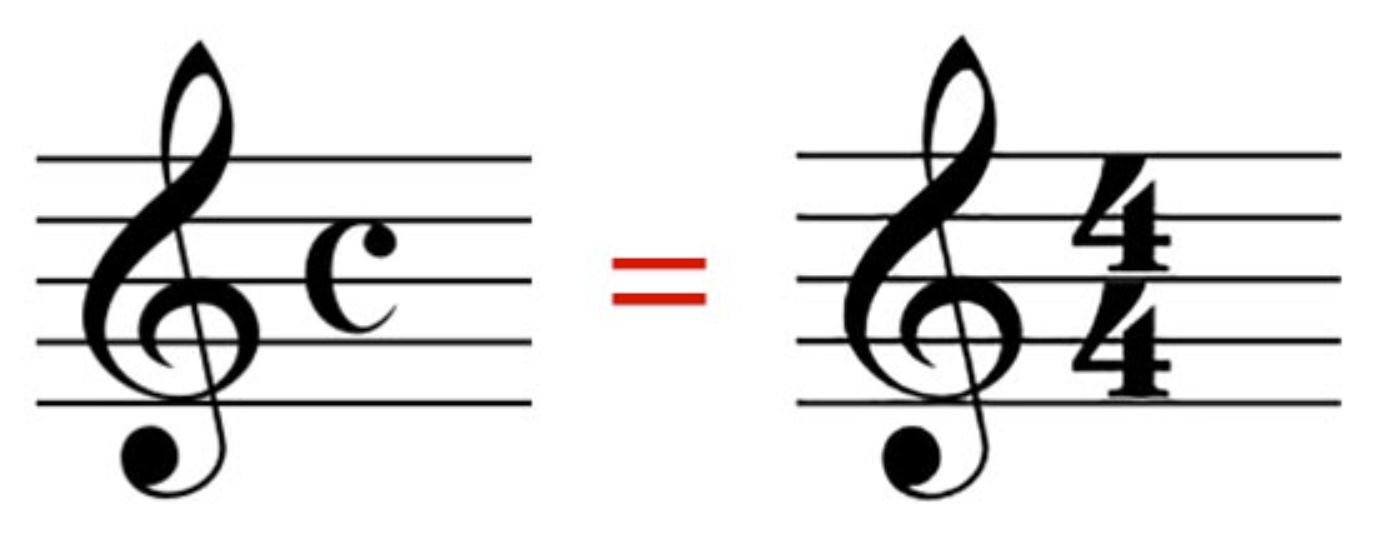

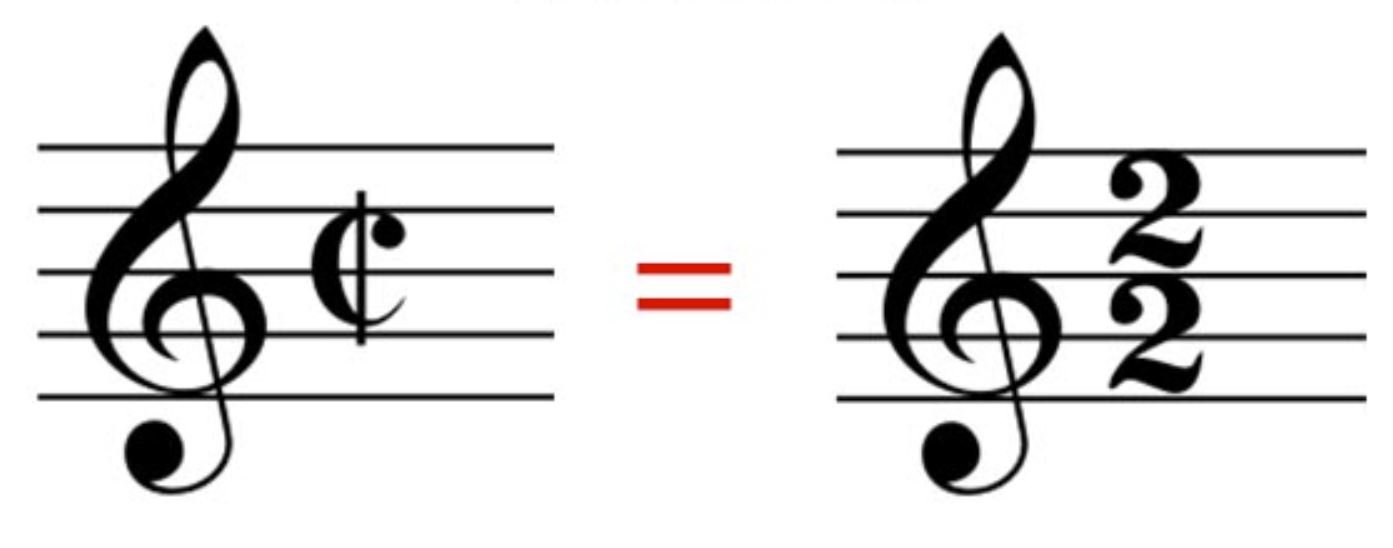

This is the way the spacing of beats and silences are organised. Time signatures and barlines govern the way the beats are grouped, and the composer chooses his or her desired combination of long and short notes. The speed of the beat or pulse is often related to the human heart beat, especially in early music. The type of rhythms used can also vary enormously, depending on the style of music - for instance, jazz will commonly have more syncopated or swung rhythms than other styles. Composers will often use repetitive rhythm patterns to create a coherent structure in the music.

Tempo

This is the speed at which music is played or sung - often indicated with a metronome mark, which describes the number of beats per minute. Tempo follows a sliding scale, from very slow to very fast and doesn’t need to be the same throughout a single piece of music. Some composers use lots of subtle tempo changes to create a feeling of ebb and flow in their music.

Dynamics

The volume of sound produced by instruments or voices, from soft to loud. Sudden or gradual changes of dynamic can create depth and variety in music, as well as enhancing the way it makes us feel as we listen. Dynamics are usually indicated with combinations of the letters - p (an abbreviation for piano - the Italian word for soft), f (forte/loud) and m (mezzo/moderately). The words crescendo and diminuendo (growing and diminishing respectively) are used to indicate gradual changes of dynamic.

Melody

Put simply, this is the tune. Melodies are created from combinations of scale and arpeggios and are often the element you recall long after you’ve heard a new piece - think of that earworm which can get stuck in your head for hours or days! A melody might be a short motif, or a longer, more expansive phrase. Melodies can be made of conjunct notes (stepwise - like a scale) or disjunct (notes which leap around by larger intervals) and this can entirely change the character.

Harmony

These are the notes which sound simultaneously with a melody, often enriching it and perhaps changing the way we perceive it. Harmonies can be consonant (pleasant combinations of sound, such as the notes from a single arpeggio) or dissonant (clashing, discordant notes which create a sense of tension). Harmony has changed over the centuries, from simple octaves in medieval music, to rich chromatic chords in the works of Romantic composers.

Texture

This is the way the music is constructed, combining one or more melodic lines and the accompanying parts together. Density of texture can vary enormously, from sparse to rich. One extreme might be a single line, played or sung alone (monophonic - literally one sound). A choir singing a hymn tune would be described as homophonic, because they are all largely singing together in chords. In contrast, a canon or fugue would be described as polyphonic (many sounds) because the voices are playing and moving independently of each other.

Whether you want or need to know the technical terms for all these characteristics will depend on the depth of knowledge you desire. But just recognising the differences will bring you a greater understanding of the music, both as a listener and as a player.

I’m going to share some pieces of music with you to illustrate many of these characteristics. I’ll include recordings, as well as links to the scores so you can follow along with them. We all learn in different ways. For those who learn aurally, hearing the music may illustrate my points well enough, but if you find it easier to pick up new concepts through visual cues, having the scores may help reinforce your learning.

The music I share below covers a wide range of repertoire. We’ll begin in the recorder player’s familiar territory of the Renaissance and Baroque. Other pieces venture beyond the recorder’s home sound world, but I hope you’ll still find them interesting and inspiring. Even if you play mostly early music, it’s a good idea to widen your musical horizons from time to time as a means of opening one’s ears to fresh ideas.

With each piece I’ll highlight one or more of the elements of music to listen out for - you may make some surprising discoveries.

Bach Chorale - Jesu meine freude

We’ll begin with texture and this is a good example of homophonic music. From the score you can see that the voices move together most of the time, shifting to a new harmony or chord on each beat - I’ve highlighted this vertical movement with red lines in the first two bars. This creates quite a dense texture, with sound levels remaining the same throughout the piece. While the notes are easy enough to play or sing, such simple music requires excellent ensemble skills to ensure everyone’s rhythms match exactly.

Byrd - Fantasia à 4

At the opposite textural extreme we have the polyphonic music of the Renaissance, where composers such as Byrd write multiple independent parts, which have a conversation, weaving in and out of each other. In this Fantasia you hear each line begin at different times, but the way they interweave creates a coherent musical whole.

Notice too how on the first page (shown below), all the voices share a single line of melody - sometimes imitating each other, sometimes playing together a beat apart. This melodic shape is highlighted in yellow in the extract below. When Byrd has finished exploring this particular melodic fragment, he moves on and uses a new tune, working with six or seven different themes during the course of this one Fantasia.

Even Byrd steps away from polyphony at times - notice how all four voices come together for just a few seconds at 1:57 to play chords in rhythmic unison, before breaking away once again into a musical conversation.

Download Byrd’s original score here.

Download and play the music as a recorder consort here.

Mozart - Kyrie from Requiem

Before I move away from polyphonic music, one of the most formal examples of this genre is the fugue. Unlike a Fantasia, which meanders from one melodic idea to another, the fugue has a very precise structure. I plan to explain this in more detail in a future blog post, but this recording of the Kyrie from Mozart’s Requiem illustrates it very well. In the video you can see how Mozart combines two contrasting musical ideas to create a conversation between the voices. The subject (the main melodic theme, highlighted in purple) is a robust and quite angular melody, leaping dramatically, while the countersubject (a melody which works against the subject, highlighted in pink) is much busier, running hurriedly in short bursts of scales, building up the excitement.

Download Mozart’s full score here.

Download and play the music as a recorder consort here

Corelli Concerto Grosso Op.6 No.8

This well known work by Corelli gives us an opportunity to explore harmony and texture.

If you listen to the second movement, which begins 17 seconds into this recording, you’ll hear how the chords perpetually shift between discords and concords - moments where the notes clash with each other to create tension, before the harmony resolves into something less strident. In the extract below I’ve circled all the notes that clash with each other so you can see just how many there are.

In the following Allegro (which begins at 1:18 in the video) you can hear the texture change from being mostly formed from chords, to something more dynamic. The violins continue to shift between concords and discords (highlighted in the extract below) but the bassline takes on a much more energetic and melodic role, powering the music along through a continuous flow of quavers. As you can see from this extract, this melodic lines uses lots of disjunct movement (notes which jump around rather than moving in scales) which gives the music a lots of energy and drive. Notice how the players also take a creative decision to make the notes quite detached, even though Corelli gives no staccato marks in the music.

Download Corelli’s Score here.

Download and play the music as a recorder consort here.

Beethoven - Piano Concerto no.4, 2nd movement

Moving away from the recorder’s natural musical territory, we turn to music with a greater range of timbres and textures. In Beethoven’s 4th piano concerto he composes for a typical classical symphony orchestra - strings, woodwind (two each of flute, oboe, clarinet and bassoon), two trumpets, two French horns and timpani. This brings him plenty of scope to create interesting combinations of tone colour, but in the 2nd movement he pares the scoring right back to the basics – just solo piano and the string section. This minimalism has a magical simplicity and there’s a real sense of conversation between the soloist and orchestra.

As you can see in the extract of the score below, at first the piano and orchestra don’t play together at all. The strings play a staccato melodic line together in octaves and their phrases are answered by a simple, legato melody in the piano, accompanied with chords. At 2:47 in the video the strings shift to just playing occasional pizzicato (plucked) notes, setting the piano free to explore alone, with more flowing melodic ideas. At 4:27 the orchestra returns, with the cellos and double basses playing a melody in octaves, while the violins sustain a single note. It’s not until 4:41 that the strings finally get to play together in harmony, accompanying the piano for the last few bars of the movement.

Isn’t this a magical effect? Beethoven composed lots of powerful music, which grabs you through its sheer force. But here he goes back to the simplest of elements and I think it’s all the more powerful for this.

Holst - The Planets - Mars, The Bringer of War

This is a piece which probably needs little introduction, but have you ever thought about how Holst creates a sense of Mars as the Bringer of War? Listen carefully and you’ll hear the way he uses many elements of music to do this.

First he uses rhythm. Listen to how the repeated rhythm which appears first in the timpani, harp and strings, creates an incessant drive - like an army marching into war. The use of a repeating rhythm like this is called an ostinato and you’ll have heard the device in many other pieces of music - Ravel’s Bolero, for instance, where the side drum plays the same repeating rhythm throughout the work.

It’s not just Holst’s use of an ostinato that creates this war-like feel. His choice of time signature is unsettling because we generally prefer rhythms which feel balanced and symmetrical - after all we have two of most of most parts of our body - eyes, ears, lungs, feet, hands. By having a time signature of 5/4, the two halves of the bar feel unbalanced - three beats followed by two - so this immediately creates a sense of tension.

Now listen to the harmony Holst uses - rather than being straightforwardly major or minor, there are many more discords, once again creating a sense of tension. Later in the movement, the focus move onto a sinister melody in the lower instruments (3:37 in the video). But if you listen carefully you can still hear the side drum and trumpets nagging away with little snippets of the original ostinato rhythm - highlighted in red boxes below.

Andy Williams - Music to Watch Girls By

After all that tension, let’s move onto something complete different, and much sunnier too. Even if 1960s pop music isn’t your thing, there’s plenty to listen out for - in particular the use of melody in this classic sung by Andy Williams.

The main melody of the song is undeniably catchy - one of the character traits of any good pop song. But listen more carefully, beyond Williams’ vocals. Did you notice that 27 seconds into the song, the backing singers and brass section echo snippets of that same melody between the song’s phrases? At 1:06 we have another classic feature of pop songs - a sudden and pretty un-subtle key change as the music is abruptly pulled up a semitone from G minor to A flat minor.

This leads us into the central instrumental section (at 1:07) where the brass play the melody, but did you notice what the violins were doing at the same time? Listen carefully and you’ll hear they have a long, sinuous melody of their own, which slinks around above the brass. This is called a countermelody, as it works against the main tune. Can you follow the violins without getting distracted by the main theme? This can be tricky to do, but it’s a useful exercise as it’ll help you learn to pick out different melodies and rhythms in the music you play.

Sergei Prokofiev - Peter and the Wolf

For my final piece of music I’m going to talk about the concept of programme music. Most of the repertoire we play as recorder players is absolute music - that’s music which is abstract rather than descriptive. But sometimes we want to paint an aural picture, describing an event, scene or emotion. We probably overlook the programme music we encounter most frequently - the incidental music accompanying films and TV shows. Rather than existing as standalone concert items (although sometimes composers create concert suites from their music to make this possible), film soundtracks are there to support the visual images we’re watching and amplify the emotions the director is trying to convey.

For instance, Alfred Hitchcock originally intended the iconic shower scene in Psycho to be unscored, but his composer, Bernard Herrmann, persuade him to try it with the score he’d written to accompany it. The shrieking violins undoubtedly add to the horror of the scene, although in reality we see almost no blood and the violent sound effects were actually created by stabbing a melon! If you want to compare the moment with and without music you can see both versions here.

Often a composer will use a specific theme in programme music to help illustrate a person, place or idea - known as a leitmotif. Wagner was perhaps the greatest proponent of this technique, using over sixty distinct musical themes to depict people, places, objects and event concepts in The Ring - a cycle of four operas. Don’t worry, I’m not going to ask you to listen to sixteen hours of opera - I have something more compact to illustrate the same point!

In Peter and the Wolf, a musical retelling of a Russian folk tale, Prokofiev not only uses a particular melody for each character in the story, but he also pairs these tunes with a specific instrument - for instance a high, twittering flute to depict the bird. Each time a character appears in the story we hear their theme and instrument, but Prokofiev also modifies these melodies to illustrate the activities of the characters. When the cat (depicted by the clarinet) climbs a tree (12:38 in the video), the clarinet line scampers higher and higher, to help us envisage the character jumping upwards from branch to branch, as you can see in the extract below. Likewise, at 26:26 the end the duck’s theme is heard with an ethereal string accompaniment, as we hear her calling from inside the wolf, having been swallowed alive.

Now it’s your turn…

I hope some of the pieces I’ve talked about have perhaps opened your eyes and ears to new musical horizons and some of the tools composers use to write music. Now it’s your turn to do a little homework…

Next time you listen to a piece of music take a few moments to ask yourself some questions about what you’re hearing. Try to be as descriptive as possible with your answers to these questions. It doesn’t matter if you don’t know the technical terms, but just having to use descriptive language of one type or another to identify what you’re hearing can be educational.

Here are some ideas to get you started…

Timbre - is the music being played by a monochromatic ensemble or has the composer written a score with lots of variety of tonal colours? For instance, a recorder consort or brass band would count as monochromatic, because all the instruments fundamentally produce the same tone, albeit at a variety of different pitches. In contrast, the instruments in a symphony orchestra produce infinitely varied tones, so composer can create different colours by giving a melody to the oboe, while the strings provide the accompaniment. Ask yourself which instruments you are hearing, distinguishing the flute from a bassoon or the trumpets from the violins.

Dynamics - how would you describe what you are hearing? Is the music quiet and ethereal, or perhaps loud and bombastic? How did the dynamic contrasts change the way you feel about the music?

Tempo - how would you describe the tempo? Is the music slow or fast? Does the speed remain constant (tap or clap along with the music to help you judge this) or is the speed more flexible and changeable?

Rhythm - what sort of rhythms has the composer used? Is the music crisp and staccato, or elegant and flowing? Do you want to march to it, or to sway along to a waltz? How does it make you feel? Don’t be afraid to move your body to the music – this instinctive movement may better help you quantify your response to the rhythm.

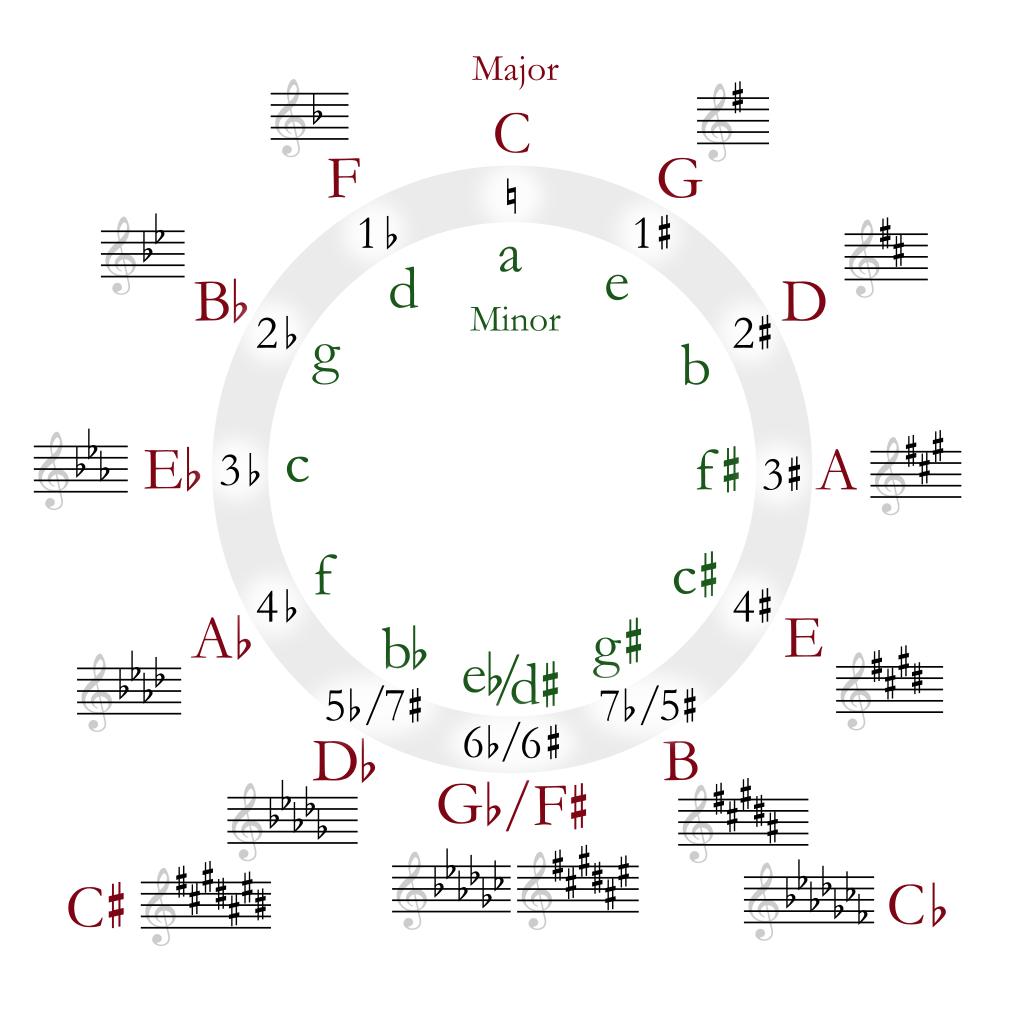

Tonality - how does the music make you feel? Music composed in minor keys often has a feeling of melancholy, while major keys can feel brighter and happier. But, as this article suggests, this concept is more common in western music than that of other cultures and there are exceptions to every rule. Think back to Music to Watch Girls By, which we listened to earlier - undoubtedly a joyful, lively song, but in a minor key.

Texture - think about the way the composer has structured the music. How would you describe the texture? You can use simple descriptive words - sparse, dense, lush, smooth, spiky. Also listen out for the way the composer has achieved this - do the voices imitate each other, or are all the parts playing together like a chorale? Or perhaps there’s a solo voice with a melody, which the lines are accompanying?

If you enjoy this exercise and find it helps you become more aware as you listen, you could perhaps get into the habit of making notes about what you’re hearing. Maybe take half an hour each week to listen to a piece of music and write down the things that stand out to you most. Which features appeal to you most? Do you find surprising commonalities between pieces music which, on the surface, seem very different? Does this process help you to understand music better and perhaps like works you might have dismissed before?

Have I made you think differently about music? I know I’ve asked a lot of questions in this blog post, perhaps more than just giving you information to absorb. Yes, there’s undoubtedly a place for mindless enjoyment of music, but understanding can help you appreciate it even more. These listening skills can be applied to any type of music, whether it’s by Handel, Brahms or Jimi Hendrix, and I hope perhaps I’ve helped you explore your musical world in a new way. If you’ve had a real ‘Eureka’ moment as a result of this, I’d love you to share it in the comments below. We all come to music from different places and I’d love to hear about your own individual musical discoveries this week.